Imagine 2200, Grist’s climate fiction initiative, celebrates stories that invite us to imagine the future we want — futures in which climate solutions flourish and we all thrive. Discover more stories. Or sign up for email updates to get new stories in your inbox.

Visitor, what is hunger?

— You don’t have to call me visitor anymore, Aru — I replied, giving myself time to think about the question. — You can use my name. Because, technically, I’m a refugee.

Fifteen years old. The whole class wasn’t older than that, and yet it was the third question of that magnitude I’d been asked in a week.

Aru blinked assertively and asked the question again:

— Redson, what’s hunger like?

— I’m not sure I understand. You want to know how people get to starve?

— No, we know that. The Great Famine Age has been discussed many times here. I want to know what hunger is like.

It could be a problem with the autotranslator, some expression that was impossible to say in Portuguese.

— I still don’t understand, Aru, I don’t know if it’s a translation problem. Do you mean feeling hungry, being hungry?

Aru lowered their head, thoughtful. Part of the class, those who had actively engaged in the conversation, followed suit. I still hadn’t got used to the time, of response, of action, of life in Freedom. While half were thinking, the other half were doing something else, like in almost any class of the same age that I knew. The difference was that no one drew attention to those who didn’t want to take part. The desire to be in the conversation determined who would be in it. Those who didn’t want to, well, they didn’t have to.

My anxiety began to dig into my chest. Fifteen young people in silence, without an answer to a question that seemed very objective to me. Suddenly, Eni:

— We all feel hungry, visi… Redson. We are living beings. What has always intrigued us, and we even did an experiment on it, is what it’s like to be hungry. To starve. What it’s like for the person who is starving and what it’s like for the person who, having access to food, sees someone else starving.

It was my turn to fall silent. The image of my mother in the bone line exploded in my mind and revived the memory in my stomach. If it was possible to express that feeling, I might be able to respond. But how to put into words a pain that squeezes both the gut and the heart? How do you revisit the worst years of your life and put them into objective terms for the class?

— How … how was that experiment, Eni? — Once again, I resorted to the strategy of buying time.

— Half of us didn’t eat for a week, while the other half ate normally. Those who didn’t eat watched those who did, and the latter couldn’t offer anything. At the end, the two groups shared their impressions.

— And what were they?

Aru took the floor.

— Physiologically speaking, hunger hurts. In many different ways. I was in the group that didn’t eat. But on the third day I realized that our experiment was destined to fail because, even though it was painful, we all knew that it would end, that it was just a simulation.

— I agree with Aru — Ilene continued. — We didn’t starve. At most, we fasted.

— When was this experiment?

— Two cycles ago — replied Aru.

I did the math: Two formative cycles in Freedom was four years. They were no more than 11 years old when they were experiencing hunger.

— Apart from this experiment, have you never been hungry? There’s never been hunger in Freedom? — I asked.

The class lowered their heads again, this time in greater numbers. There was still a group that preferred to talk among themselves, a little oblivious to the debate. I was still impressed by the whole thing. No one was in a hurry to answer, no one gave in easily to impulsiveness; there was no reason for it.

The one who broke the silence this time was Ngozi.

— I’d say it’s impossible to starve in Freedom. I don’t know about all the stories here, but in the communes I know or have heard of, there is a tradition of planting three fruit trees for every person born. So there’s always food, even to share with other communes when the harvest isn’t enough.

— In my commune it’s not fruit trees, but any edible plant — Ilene continued. — But I agree with Ngozi: It seems impossible to starve in Freedom.

— At the time of the experiment, we even asked the Council about hunger. The answer we got was inconclusive: No record of starvation, which doesn’t allow us to say that there never was any — added Aru.

— And why do you want to know what it’s like to starve, then?

— I asked the question precisely because it is a distant situation — Aru replied. — We know that water, land, air, everything is bought and sold outside of Freedom. That there is plenty for a few and misery for everyone else. That the Climate Disaster has affected places and people much more than it has affected us. But what I want, what we want to know is more tangible: What hunger is like, what it feels like, what other people’s relationship to hunger is like.

It wasn’t the autotranslator the problem. The device worked perfectly.

— I … I don’t know if I can answer that. I need to think about it.

The whole class nodded in agreement. Irma looked at me asking if I intended to follow, and I said no with my eyes. She got up from the back of the room, walked to the door and turned to the class:

— It seems like a good time to … eat. What do you think? We could take the opportunity to present Redson the dishes we’ve brought today.

The class broke up and stood up calmly. Irma approached me and beckoned us to follow. We crossed the Formative Hub to its other end, passing several groups on the way, where people of all ages were discussing, calculating, experimenting and having fun.

We found the cafeteria empty. It was a colorful space, the walls covered with various paintings depicting the diversity in Freedom: People, animals, plants, food. Around the tables, cupboards and refrigerators indicated what was inside: Fruit, bread and pasta, hot dishes, cold dishes, leaves, vegetables, drinks. The classes themselves brought what they wanted to share from home.

I sat down at one of the tables and Ngozi approached. She opened a bag made of light green leaves and displayed a steaming yellow mass with a damp smell.

— Have you ever eaten pamonha, Redson?

— Never. What is it made of?

— Green corn.

— Is it sweet or salty?

— You can eat it both ways. I eat it sweet, like the elders in the commune — she held out her arm and offered me a pamonha and a spoon.

I was sure I knew what corn tasted like until I tried it. It was nothing like the artificial corn flavor that marked our lives during the Great Famine. Not even the color was the same: The yellow was bright, tasty, soft, very different from the pale yellow that discolored our plates years ago. Irma sat down next to me.

— So, have you tried real corn before? — she asked, trying to get closer.

— Not yet … — I replied, licking my spoon.

Aru sat down in front of us and showed us another yellow plate.

— Is that corn too?

— Yes … it’s called curau. I made it myself.

Little by little, the table was filled with young people and plates. It was the seventh time I had sat down to eat with one of the classes, the seventh time that a world of new flavors had presented itself. The difference was that this time I was eating with hunger in mind.

I tried the curau after the pamonha, and continued around the table, listening to stories about the dishes and their history. Eni’s quinoa, Ilene’s angu, Anika’s fruit cake, Maali’s açaí and cupuaçu. Recipes we had heard about as children in São Paulo, but which only our grandmothers had tried. My tongue tingled with desire at every new texture, every surprising taste that was nothing like anything I had ever put in my mouth. When everyone seemed satisfied, I said goodbye, promising to return the next day with an answer to the question they had asked.

I spent the rest of the day alone with the hunger in the lodge. I had lunch and dinner, but it never stopped being with me. I revisited memories and sensations that I didn’t remember, probably because they weren’t good. Our brain knows what it’s doing.

Outside, I could hear people dancing to a rhythm that reminded me of samba, but wasn’t. I let it envelop me, trying to forget the hunger.

I failed.

The week at the Formative Hub, my first in the commune of Ganga Zumba, an agro-city that I never dreamed could exist, was intense. The density of the discussions and discoveries of the last few days helped a little to distract me from the feeling of nostalgia, which, until then, I didn’t really know what it was — after all, there was nothing left for me to long for in São Paulo.

Freedom didn’t seem like a dream. It was real, more than any dreamlike experience could ever be. After seven months, I was beginning to understand how this was possible. I experienced choices unimaginable anywhere else I knew or had heard of.

The first was whether I wanted to stay.

I spent two days at the Reception Center until I made up my mind. I knew almost nothing about freedom there. It was a safety measure in case I decided to leave, but maybe it was more than that, maybe it had to do with the time, which ran differently there. After saying yes, I began to explore the territory. First, I had to attend Free Sign Language classes, the territory’s common language. It was a compulsory course for outsiders. Only then I could move around any commune I wanted. Ganga Zumba was the third one.

The history of Freedom was a great mystery. At the Formative Hub, among the neighbors, at the living quarters of each commune, at the fields, at the Council, in the streets, there were many versions of the origin of the territory. The derivation seemed to be related to the origin of the people: Depending on the commune, the ethnic group to which they belonged, their gender or lack thereof, the founding myths of the place changed. All of them, however, converged when I asked where we were:

— Older people call it Freedom; younger people call it Home.

I didn’t feel at home. But despite the short time, I was beginning to feel free.

I can’t say I woke up early the next day, because I’m not sure I slept. I tossed and turned in bed thinking about hunger for hours. At around 9 a.m., I left for the Formative Hub without having any breakfast.

The sight of that place was not at all reminiscent of a school, although I associated it with one. There were no bars. No buzzer. There were no grades, no roll calls, no exams. The classrooms, large and small, were all decorated according to the classes on offer. You could recognize a proto-marble shop in one corner, a chemistry lab in another. The course I was taking, “Cultures and Ways of Life Around the World,” was held in a different space each time. That day, the meeting would take place in one of the gardens.

I found the class in an uproar. One group was playing a card game I didn’t know. Another was listening and dancing to a rhythm similar to the one from the night before. Aru was holding a book about the Great Famine, Ngozi was leafing through an old novel about a planet where there were no borders or private property. Irma invited everyone to sit in a circle, which gradually happened, and I stared at the group for a few seconds before speaking.

This time, the attention was all on me.

— I’ve thought a lot about your question, Aru. And I think I have an answer. I don’t know if it will be enough, or if it will make sense. But it’s what I can tell you about what hunger is like.

I sighed for a moment before actually starting.

— I’ve come to the conclusion that there are many types of hunger. Perhaps as many as there are people experiencing them. It ends up being impossible, then, to express absolutely what hunger is like. I can only say, or at least try , what my hunger is like. And my hunger is twofold: that of someone who has had nothing, or almost nothing, to eat; and that of someone who has had enough to not feel the physical pain of hunger, but never to avoid all the other pains related to it.

The class remained silent, focused. I continued.

— My first hunger was intertwined with my childhood. I can’t remember a time when I didn’t feel my stomach when I was little. I remember my mother trying to entertain me by recreating scenes from an old children’s story, where the children didn’t grow up and the food was imaginary, but satisfying. I had many magic bean soups at that time, which were nothing more than salt water mixed with something else. I wondered how to express this hunger to you, beyond the stomach ache, the weakness, the inability to concentrate on anything and the desire to sleep to not have to feel it. And the image that came to mind was of a curtain, sometimes lighter, sometimes weighing a ton, which I could never get through. On the other side of it was a world that I now know was a lie, but for which I would have given anything at the time: A huge supermarket where I could fill my cart with anything I wanted, and where all the imaginary tastes that my mother created for me became real. Living with this hunger was like living split in two, being at the same time in a physical world that translated into pain all the time and in a fictional world where it was possible to feel something other than my own emptiness. I think it was this second world that made me not give up on the many days I felt powerless.

Aru stared at me between bewilderment and compassion; Ilene seemed to express horror. Ngozi looked through me, as if trying to make sense of what I was saying.

— The second hunger of my life came after I had grown up and discovered strategies to, if not end, at least reduce the effects of the first hunger as much as possible. And it was a collective hunger, shared with almost everyone who lived in my neighborhood, in a kind of complicit dream that we almost never expressed in words, but was always present in any exchange of glances. This hunger was announced from the other side of the bridge that divided São Paulo, where we could see, inside the domes, the thousands of plantations cultivated to feed those who lived in the center. They were natural gardens, the last in the city, set up on the reclaimed land where many of our families used to live. While we were eating Human Ration that tasted like nothing and smelled like nausea, made from transgenic waste and enriched with the minimum necessary vitamins to keep us organically fit to work, those gardens produced enough to feed the city’s population twice over. I know you’ve studied the Great Famine, so I’m going to focus on what we felt: Having everything so close and yet completely out of reach caused a collective sense of mirage, of being in a desert and seeing the oasis just a horizon away — a horizon that never arrived, but that kept announcing itself, generating a kind of infinite loop of impotence mixed with hatred. Our hunger there was to break through the desert, to share the oasis, and it increased every time someone died of malnutrition. That’s how I lost my youngest brother. The magic bean soup, unfortunately, wasn’t enough…

I lost the words remembering Lino, and lowered my head. The class’s expressions were now of anger and indignation.

Aru again broke the silence.

— Redson … I have to tell you that I’m sorry. Not for what you’ve lived through, I don’t have that right, but for asking you to relive such painful feelings. But if you don’t mind, I’d like to ask you another question.

I raised my head again and looked them firmly in the eye. They didn’t look away. They seemed to seek permission in mine.

Granted.

— Go ahead, Aru.

— Do you … still feel that second hunger?

I got up from where I was and walked towards one of the windows. On the other side of the glass, the landscape of the agro-city built in the middle of the tropical mixed ombrophilous forest loomed, so different from the aridity of the glass towers and car-colored autobahns that filled São Paulo. A few kilometers away, agricultural drones flew over gardens of all kinds, some with plants I had never heard of, like black corn and curly kale. In front of us was one of the many Communal Cores, which concentrated dozens of public utility spaces around a square, such as workshops, warehouses and barbershops. I crossed my arms behind my body, as I always do when needing to regain my strength, and turned back to the group. Aru searched my eyes again.

I stared at them with the same complicity they offered me when we shared the curau before answering:

— All the time, Aru. All the time. And being here, in a way, confuses me.

— Why? — Ngozi asked.

— Because there is no hunger here, there never has been, as you yourselves have said. But everywhere else in the world there is. It seems selfish to experience all this after having lost everything I had, all the people I ever loved fighting hunger.

Lino came back to me. My mother. My uncle. All the comrades killed in the guerrilla war. This time I couldn’t hold back the tears.

The class maintained a strangely infinite and welcoming silence. When I was able to face them again, Aru approached me.

— Redson, we’re sorry. Our curiosity has crossed the line.

— I … I don’t…

Silence.

I burst into tears like I hadn’t done for years. So many that I couldn’t remember how many. Aru hugged me, then Ngozi, Eni, the whole class. The more welcomed I felt, the harder it was to contain myself. I surrendered in a way I didn’t even know was possible.

Irma intervened.

— It seems to me that the topic here is no longer hunger. I suggest we take a break.

The class agreed without saying a word. Gradually, the collective embrace broke down and I was able to regain some of my control. Irma led me out of the room.

— Are you all right?

— I … don’t know. I don’t think I ever really processed everything I lost before Freedom. Everyone I lost. I don’t know if you understand.

Irma held both my hands and searched my eyes.

— We all know death. Here as well as there. Anywhere — Irma looked deep into my eyes. — I have an invitation for you.

The weeks in Freedom were marked by the lunar calendar, and there were no months: The counting of days was linked to the seasons. It was the fourth day of spring. It was hot, but not too hot, and the sky was clear on that NewMoon-1 evening.

I arrived at the party, which had already started, and found small groups of all ages scattered around the square. They shared food, drink and hugs, in small picnics that everyone circulated around. In the center of the square, a huge circle of people danced arm in arm to the sound of some drums and a harmonica, a completely new mix for me. Whoever was outside went in, whoever was inside came out, and in this movement the circle never broke. All around, there were also people dancing alone or in pairs, with a particular choreography that gave onlookers a feeling of ecstasy.

I was never much of a dancer. I didn’t like the feeling of being watched, even knowing that nobody was noticing. That circle, however, was different, a collective dance. I was admiring the movement closely when someone pulled me by the arm. It was Irma.

— Welcome to the Day of the Dead!

— Day … of what?

— Of the Dead. There’s one every season.

— But it looks like a party.

— It doesn’t look like it. It is.

Irma took me by the hand and led me among the dancers in a kind of introduction, greeting one by one with a nod and instructing me to do the same. I obeyed, withdrawn. Suddenly, I was part of the dance, a member of the ritual.

Once inside, I noticed a bottle of booze circulating among the dancers. Each one took a sip, sometimes two, and passed the bottle around. It reached me and I smelled something similar to cachaça, but more fragrant. I took a small sip and it went down smoothly, didn’t seem strong. I decided to take another sip and moved the bottle to one side to continue dancing. Within a few minutes, my body seemed to levitate, as if my feet weren’t touching the ground and I was dancing in the air. I keep that feeling with me to this day.

I was experiencing the peak of excitement when everything stopped. The circle, the picnics, the dancing pairs. The drums now set a hard, heavy, ceremonial rhythm. Outsiders joined in, and now it was no longer arms that united us, but hands. Little by little, without any order, one by one, people broke free from the circle, went to its center and shouted a name, fist raised, once, twice. The whole circle, in the most powerful unison I’ve ever experienced, responded:

— Present!

Levitation became gravity. I felt my body as heavy as lead, as if I had no legs but roots and was stuck in the ground. Little by little, I managed to break free and, as if it were a call, I left the circle to go to its center.

— Ortencia! — I shouted at the top of my lungs.

— Present! — Replied the circle.

— Lino! — My scream wanted to tear the sky apart.

— Present! — Returned the circle.

It was like they knew my mother. My brother. As if they were there.

One by one, I shouted the names of everyone I had lost, of every person who had fallen in the struggle, until I had none left.

When I got back to my place, my face was streaked with tears. Not the same tears as the day before, or when Lino died. Others, as light as a feather, with the taste of freedom.

As soon as the ritual was over, the circle broke up in hugs. An unknown person came up to me.

— Are you all right?

— I am. Are you?

— I am too.

We hugged and, instead of crying, my body seemed to want to explode with longing. Of fullness. Of communion.

For the first time in my life, the emptiness in my stomach wasn’t hunger, but nourishment.

The next day, I woke up feeling lighter than ever.

And just after breakfast, I got the news.

My senses, dulled before the Day of the Dead, have been even busier since then. My last days in the Formative Hub, also the last in Ganga Zumba and in Freedom, seemed to be a single, infinite moment, lost somewhere between the discovery of entirely new feelings and the expectation of returning to a future. Of glimpsing one.

Community wasn’t something new for me. Before the guerrillas, before all the death, I had experienced one. But the sense of living collectively had taken on a different perspective in Freedom. It wasn’t a question of learning, of logical reasoning. All the practical experiences, all the life alternatives that I had known in those months there and had seemed part of a distant, impossible reality for me, a kind of utopian vacation that, I knew, would end one day, now presented themselves as a possibility.

I was trying to process all this when Aru walked towards me and greeted me using Free Sign Language. The greeting was impossible to translate into any spoken language, a kind of greeting wishing luck and asking permission to connect. I nodded in agreement and Aru pointed to my switched-off autotranslator. I turned on the device and they addressed me, now speaking:

— Are you really leaving?

— Yes, I am. Next FullMoon.

— Why?

— Because I’m no longer a refugee.

I handed him the holographic monitor, from which the news jumped out. The guerrillas had overthrown the government in São Paulo. After three years, thousands dead, the domes were in the hands of the rebels and in the process of being collectivized. Nothing compared to the abundance of food in Freedom, scarcity was still the norm, but now a little for everyone and not all for the many. All the people who had to flee in order not to die, myself included, had the chance to return home.

— Didn’t you say there was nothing else for you in São Paulo?

— Now there is.

Aru’s expression was one of frustration.

— I don’t understand, Aru. Why are you upset? It’s good news, you see: Hunger still exists there, but at least we have a chance of overcoming it.

— I know. I even brought you a present.

Aru opened the bag they were carrying on their back and handed me a package.

— What’s that?

— Open it.

I obeyed. There were seeds of various kinds, separated into categories: Plants, fruit trees, leaves, tubers. At the bottom of the packet, handwritten in perfect Portuguese, the phrase: “Try to change tomorrow.”

My eyes watered.

— It’s not much, I know. But it’s a gift from the whole class. Everyone brought something.

— I don’t even know what to say. It’s the most beautiful present I’ve ever received.

Aru smiled in annoyance.

— There’s no need to overdo it.

— I’m not exaggerating. But I still don’t understand your annoyance.

Aru frowned.

— You’ll think it’s silly.

— Will I? We’ll only know if you tell us.

— It’s just that I … I … I discovered that I’m also hungry.

— Hungry? What do you mean?

— Hungry to see the world. To get out of here. To go … with you.

I positioned myself to face Aru head-on.

— Aru, you’re home. There’s nothing in São Paulo that you can’t have here.

— Of course there is. People. Like you.

The answer paralyzed me. There was something of loss in his gaze, more than frustration. I thought of many things to say. None of them were enough.

I decided to open my arms, offering a hug. Aru accepted. We hugged for a long time. This time, without sobbing. Then Aru made the sign “see you on Earth,” one of the farewell greetings in Freedom, and left.

Two days later, it was my turn.

I left Freedom much heavier than when I arrived. Part of the weight I carried in my luggage, full of gifts like Aru’s or the bottle of scented cachaça that Irma gave me. The other part, the bigger one, was inside me.

It wasn’t an anchor weight, the kind that drags you down.

It wasn’t the weight of hunger, mourning or loss.

It wasn’t the weight of goodbye.

What filled me in Freedom, on the other hand, was the chance to be.

Everything I’ve lost. Everything I’ve found.

Everything that I could now become.

In Freedom, I left my void.

I brought tomorrow in its place.

Danilo Heitor is an elementary school geography teacher in São Paulo, Brazil, who likes to think about the future from an anarchist point of view. Heitor has seven books published in Portuguese, two short stories published in English, and hopes to live in a world where many worlds fit.

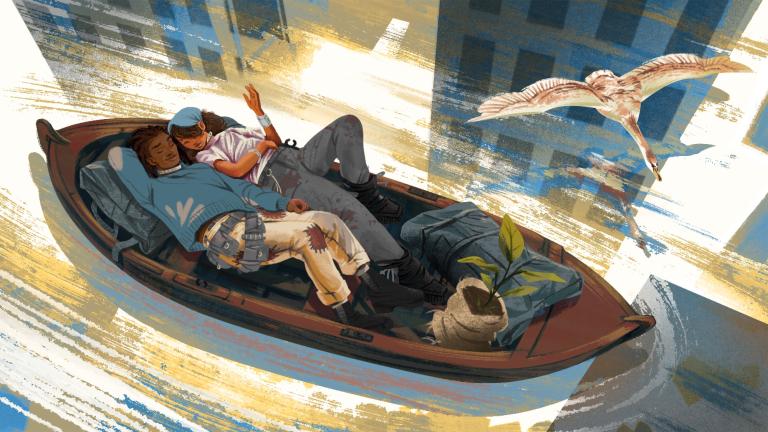

Stefan Große Halbuer is a digital artist from Münster, Germany, who has worked for brands like Adidas, Need for Speed, Samsung, Star Wars, Sony, and Universal Music, as well as for magazines, NGOs, and startups. Recently, he released his first solo book, Lines, a coloring book with a selection of his art from the last years.